This article was originally posted to Live Design Online and can be found here.

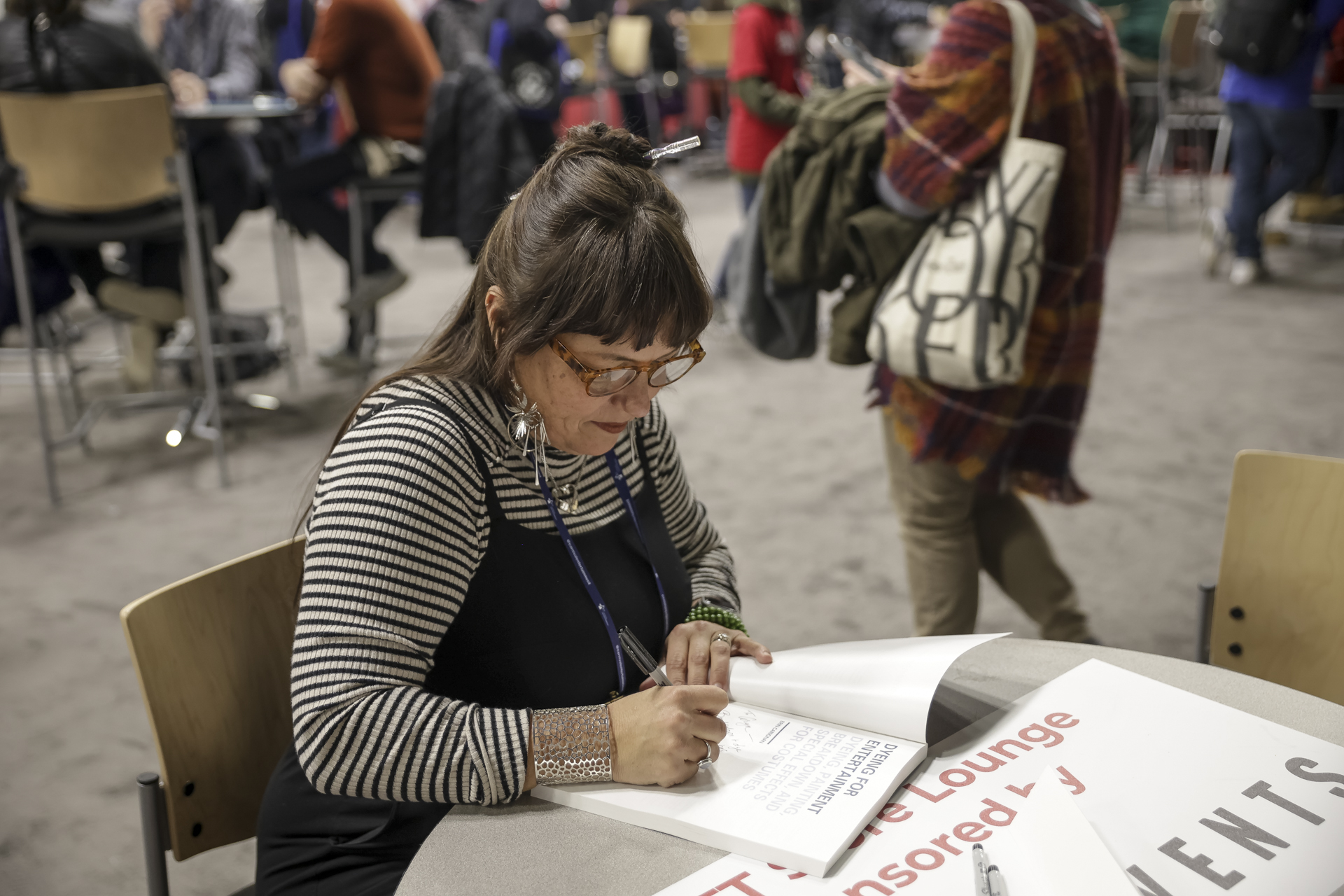

Sound designer Natalie "Nat" Margaret Houle was be honored during the 2025 USITT Conference & Stage Expo, in Columbus, Ohio, on March 6, 2025. Nat has a tremendous facility with a wide variety of technologies for music and sound design, both analog and digital, and she somehow manages to stay current on the latest developments in the field. It is my pleasure to interview her for Live Design.

Live Design: How did you first get interested in sound design for theatre?

Natalie Houle: My story starts in a house of worship setting. My mom and dad met when he was behind the console and my mom was singing onstage in a contemporary worship band at their church in Poughkeepsie, New York. I grew up watching my dad coil XLR cables, being held by my mom as she rehearsed behind wedge monitors, and witnessing the various events that they were involved in. While I was basically exposed to live sound from the moment I was born, I had an identifiable shift towards audio in seventh grade. Being a clarinetist in the pit band for the school musical wasn’t floating my boat. From the pit, I eyeballed my friends back in the sound booth of our auditorium and felt like that was where I was supposed to be. I didn’t want to be in the spotlight or up front; I wanted to help facilitate the show the way I saw my dad doing every week: invisible, yet crucial. I approached the tech folks, who were all boys at the time, and basically decided that this space would be my scene. The problem with that was that I recognized the tools but I didn’t know how they worked. So the next Sunday, my dad explained to me what a lavalier mic was and how our preacher’s mic was different from the ones I described from school. I kept slowly learning and watching after that. Sometimes he’d let me press record or stop on the CD recording for the sermon, which was a big adrenaline rush at the time, or to burn copies for the worship team. The following year, when I was in eighth grade, we were doing a production of Wonka and they needed a chocolate waterfall sound effect for the big reveal. My dad and I built the cue together, and after going through the process, I knew I had to keep doing this. Throughout the rest of grade school, I would be playing both sides by participating in music ensembles and being in the booth with the tech crew. My motto quickly became: who could possibly be cooler than the only girl in A/V Club?

LD: You went to college for your undergraduate degree in sound design at SUNY New Paltz, and while there, you received the Pat MacKay Scholarship for Diversity In Design, sponsored by Live Design Magazine, TSDCA and USITT. How did things change for you after you received this scholarship?

NH: Pat MacKay was the first scholarship I ever received, and it was a crazy feeling. I wouldn’t have gone through with it if it wasn’t for my professor, Sun Hee Kil, encouraging me to apply for every scholarship that I heard about. When I got the email that I would be one of the recipients, it felt like my first real gesture of belonging to TSDCA and to this small percentage of the industry called women in sound. It made me realize how much I cared about seeing other people who didn’t look like “a typical sound guy” succeed. It included many other benefits that were invaluable for years following: it gave me the confidence to connect more with the TSDCA community, it provided me with exposure and a platform that I have no doubt supported my future graduate school acceptances, and it gave me much needed financial support both as I paid my way through school — plus three years of TSDCA membership. The entire experience made me feel like I could be someone who stood up for my beliefs and actually be heard. That’s the most important thing the Pat MacKay Scholarship does: it places underrepresented communities at the forefront. Because I suddenly believed it wasn’t impossible for me to be chosen for something like that, I would apply for and receive five more instances of research grants throughout undergraduate and graduate school. I will always be an advocate for this multidisciplinary scholarship, and it will always be a highlight of my experience as a theatre sound student. It meant so much to me then, and still does today — almost exactly five years later.

LD: As part of your graduate thesis, you created a comprehensive website on spatial sound and then chose to share this information as a public resource. Tell us about how you created this website and why you decided to share this with everyone.

NH: The original motivation behind nmhspatial was actually disappointment about the relationship specifically between spatial audio and Broadway. Every year that I have lived in California, I’ve returned to New York to see my family for the holidays. While there, I see as many plays and musicals as possible, frequently by shadowing the A1. Year after year, I felt dejected that I was witnessing a disproportionate amount of object-based discourse in California compared to New York. I wanted to live in a world where it had become the norm for theatre, or at least a world where designers felt like they actually had the option to go spatial whether they did or not. While a few standout designers are using object-based audio as the backbone of their Broadway plays and musicals — such as Cody Spencer using L-ISA or Gareth Owen with d&b Soundscape — the vast majority of shows are largely bus-based and using either distributed mono or “stereo” output schemes. This is the case for many reasons, and my disappointment doesn’t come from a place of judgment; it’s not like designers don’t want to use spatial audio, and they have every right to think it’s overrated if they want to. But what I sensed, and still believe, is that designers are excited about spatial audio when they have the opportunity and space to be. The multifaceted problem is that they don’t feel empowered to pursue it because of both actual and perceived obstacles.

From a place of wanting to understand this phenomenon better, I started my research process solely as a personal project — not knowing what this would turn into — by asking New York and regional sound designers what they felt was holding them back. I got all sorts of answers, but they generally fit into a few different boxes of concerns. I want to reiterate that some of those barriers are real, and others are assumed widely without direct experience backing them up. Clearly, there was tangible work that could be done by a person like me — someone not actively trying to push a product — to challenge the later.

I returned from my holiday break in the winter of 2023 pumped up about advocating for this, which is when the conversation with Vincent Olivieri, my thesis advisor, really began. Originally, I imagined it to be a 20 to 30-page academic paper. I thought it needed to be super academic to be taken as seriously as I felt about it. But during our first or second thesis meeting later in fall 2023, Vinnie had the brilliant idea of this being a website. And then I blurted out, “And it can be public so everyone can hear about this, including New York designers!” By then, the topics of the early chapters were shaping up, and I became obsessed with what would be included on this website and how to make it manufacturer-agnostic. On the about page, you can learn more about how I moved on from there in my research, conversations, training, and production experiences to end up with what it became. There are so many people in the audio community who were involved; it took a village.

nmhspatial is free to access — though donations are certainly accepted — and will never have ads or a paywall for many reasons. The first is that as a woman in sound, I know how I felt attending spatial audio workshops where I was the only woman in the room. I know how distant this topic felt before I had a show to use it on, and I know how long it took for these concepts to sink into my brain. All of those social and learning considerations disproportionally affect marginalized groups in our industry and suppress prolonged engagement. So if I was going to go through the effort of creating this for my year-long thesis project, I was not going to gate-keep the information.

My next reason for sharing it with the world is that spatial audio is a lot easier to make happen than many perceive it to be. There are so many free and low-cost solutions you can use with already existing equipment and a few shifts in design approach. I covered that topic extensively in the hopes of really driving it home: it’s available to everyone. You just need to take the leap and explore it.

Additionally, I want others to experience the way spatial audio makes me feel on a sensory level — whether it’s brain tingles, tugging at the heart-strings, the intimacy of sound coming from exactly where it looks like it’s coming from, or the childlike wonder of “being” in a larger acoustic space than you’re physically in. Everyone deserves to feel that way about how sound is impacting them. I want others to discover that joy, but especially the people who are least likely to be provided that opportunity in the first place. All in all, if I can help encourage young women or any other underrepresented group to engage with spatial audio — even if it’s just one person who takes it and runs with it — all of that time was worth it.

LD: You’ve spoken about how important the issue of feminism is for you. Has there been a difference in how you perceive that issue between undergrad, grad school, and now the professional sound world? Have you observed any changes along the way?

NH: The older I get, the more I recognize that it is easy for white women to lack intersectionality in how we view our place in male-dominated industries. No matter how many all-male spaces I encounter or how many times I’ve been discriminated against because of my gender, I still benefit from my whiteness. The fact that I am where I am now is in large part because of opportunities, resources, or people that were available, or more readily available, to me because of my skin, despite being female. White women should be aware that they live in the dichotomy of that privilege and their own feminism, which brings us to intersectional feminism. I do, factually, belong to an underrepresented group of people in this industry. However, I am the very tip of the iceberg of visibility for voices that should be at the forefront: communities whose perspectives have been suppressed systemically and strategically. What I am always working on is the intersectionality of my feminism, which means knowing that before I am a woman, I am white — and that I, too, need to be either highlighting other voices or simply getting out of the way so they can be heard.

LD: During your schooling as well as after graduation, you’ve worked closely with audio manufacturers on various projects. What have you learned from these experiences? How can audio manufacturers benefit from working with students?

NH: One particularly impactful lesson was shown to me by example from Vinnie. He showed us that manufacturers actually want our feedback about their products. The consumer is a part of their ecosystem. Duh, Nat! But this idea was totally new to me when I entered grad school — now, my voice and even product development ideas as a consumer mattered. At the very least, I had the right to express what worked as a user and what could use improvement. That opened up a whole new world for me in which manufacturers weren’t scary people at trade shows who I had no idea how to interact with. Instead, I could see them as human beings on the public-facing side of these companies — companies that rely on consumers and clients for their success, and that have to innovate to keep up. We’re allowed to ask: Why is this the way it is? What if it were this way? How could this be more streamlined? What’s slowing me down as I work to accomplish XYZ? Those sorts of questions are exciting to think about openly, at least for me. Going through that thought process helps everyone involved to understand our tools at a higher level, even if the things we’re identifying are flat-out frustrating. We all have a place in this manufacturer-consumer relationship no matter what scale we’re working on or how frequently we are working with new equipment, and we should assume permission to take up that space. I wish more students knew this and felt empowered to challenge the tools they’re working with, whatever they may be.

I’ll say something to both groups. Students: your experience with the products you’re using matters. How long it takes you to learn the product matters. Accessibility barriers you find while learning the product matter. The resources that are readily available to you when you’re in a pinch troubleshooting matter. When there are shortcomings in any of those areas, you’re allowed to speak up about it. You should feel empowered as a consumer. Manufacturers: hear out the next generation, which is a growing percentage of your ecosystem year after year. Be open to the fact that you will learn from the students you talk to — as long as you talk to them longer than the time it takes for them to snag the swag at your trade show booth! We can all learn so much from those who are younger than us.

LD: As the winner of your second award from USITT, you’ve already accomplished a lot in your career. What are your goals for the future?

NH: My goals for the future include seeing the long-term projects I’m currently working on come to fruition. These endeavors are with four of the non-profits that I’ve found valuable community in: TSDCA, Audio Nerd Book Club, SoundGirls, and USITT. As I progress in my journey, I find myself having integrated these organizations into my everyday life; they have become vital to me. I hope to find myself at a more advanced level and still actively involved with them; I am growing up beside these folks, and I am so inspired by the work of my peers as well as those significantly younger and older than I. My first SoundGirls blog is actually coming out in just a couple of weeks, and I’ll be covering how folks can break down their desire for community — which I believe we are all feeling strongly about at this moment but in completely different ways — and identify how to effectively give and receive support in those community spaces.

The main advocacy concerns I’m working on through those projects include accessibility in audio education (which exists in many forms), providing opportunities for my fellow sound designers to engage with spatial audio, and being in active service to community needs wherever I can be. That includes simply asking people what would be useful to them right now, and then trying to gather the resources together to create that thing.

Circling back to the first question, my goal is to make impacts that are invisible, yet crucial: impacts felt in the way that students experience learning resources, the way sound designers manifest their spatial audio imaginations, and the way we gather together to talk about what we can do better for each other.

Off

More News

Support USITT

For many 501(c)3 nonprofit organizations, USITT included, donations are a lifeline. We are able to continue to expand our online offerings to our Members and to our industry thanks to Membership dollars and the generosity of our donors.